Case Study

1. Introduction

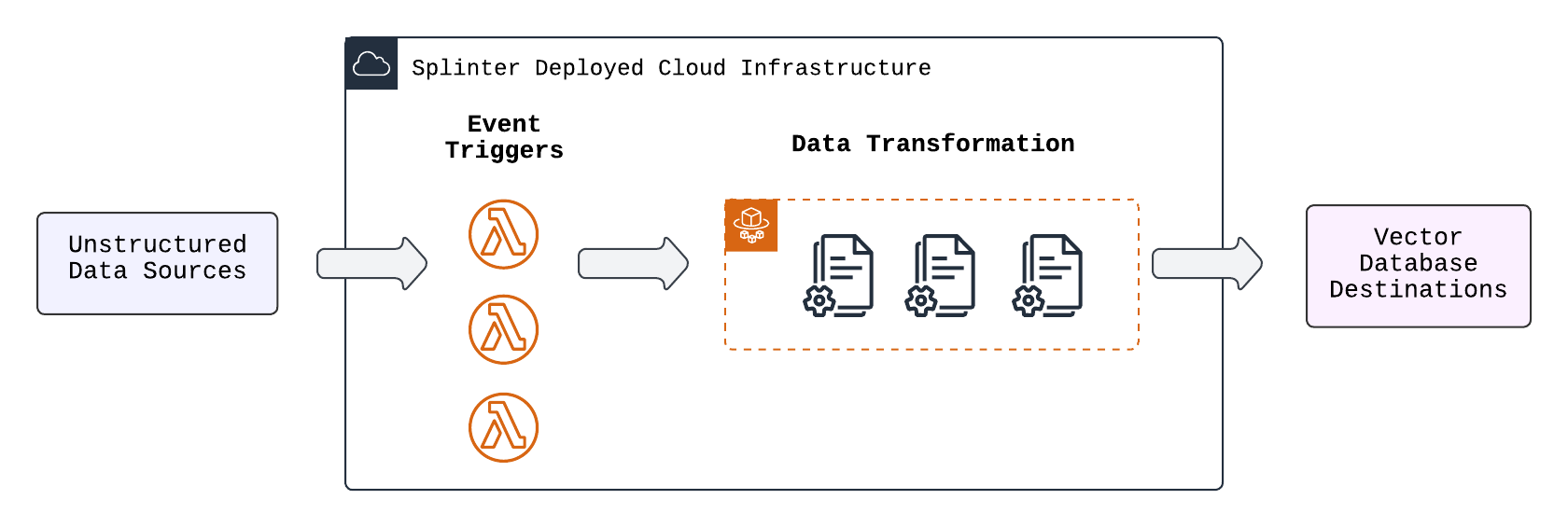

Splinter is an open-source ingestion pipeline designed to transform unstructured data into vectorized formats for integration with knowledge bases. By automating document ingestion and vector embedding, Splinter enables teams to easily convert raw, unstructured content into a format optimized for AI and machine learning applications.

The pipeline accepts a user-provided source container, where documents are uploaded. Once a document is added, Splinter processes the content by extracting meaningful features and converting them into vector embeddings using advanced machine learning models. These embeddings are then stored in a user-provided database, making them ready for integration with downstream AI systems.

Splinter is ideal for teams looking to integrate unstructured data into AI-driven knowledge systems. Whether for enhancing internal search, improving content-based recommendations, feeding machine learning models, or more, Splinter streamlines the transformation of raw data into structured, AI-compatible formats. With its open-source framework and flexible design, users can easily tailor the pipeline to their specific needs, offering full control over the ingestion and embedding processes.

2. Background

To better understand the value Splinter provides, it is important to recognize the challenges that teams face when integrating unstructured data into AI systems. These challenges include handling varied data formats, managing large volumes of raw content efficiently, and converting data into machine-readable formats for AI.

2.1 AI Applications

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has quickly become a transformative technology, rapidly changing the way that almost every industry in the world functions. AI applications are able to make sense of large amounts of data and are designed to allow us to easily interface with these data sets in more intuitive ways. Some can respond to complex instructions with comprehension that seems almost human-like, while others can retrieve and synthesize relevant information from large data sources in real-time, produce personalized outputs based on analyzing a user’s behavior, or determine the nuance or subtext behind a question. At the core of these applications is the ability to process and comprehend data, then present it in a useful, clear, and engaging way that optimizes the user experience and supports informed decisions or actions.

Some of the most prominent AI systems are:

- Large Language Models (LLMs) that train on vast amounts of data and generate responses that closely mimic natural communication.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems which take relevant information retrieved from knowledge bases and combine it with machine-generated content to provide an improved response.

- Recommendation systems that suggest content based on a user’s viewing behavior, recommend articles based on reading history, or match job opportunities with a user’s work profile.

- Semantic search which retrieves relevant results based on the context, phrasing, or intended meaning of a query, rather than relying on specific keywords.

2.2 Knowledge Bases

Many of these AI systems rely on knowledge bases, large wells of data that are structured to facilitate the retrieval of information. While LLM’s primarily rely on patterns learned from their initial training data, they can also work in conjunction with knowledge bases to enhance their performance, particularly in applications where real-time or domain-specific information is required.

A high quality knowledge base serves as the foundation of many of these applications to provide accurate information, but equally as important is the ability to effectively retrieve this information. For instance, in a RAG system, the knowledge base is used to retrieve the most relevant documents to generate a higher quality response. In semantic search, the knowledge base helps enrich queries with contextual information, allowing the system to understand the relationships between terms and retrieve results based on meaning rather than simply matching keywords. Knowledge bases can take many forms, depending on the application. Common examples of content stored in knowledge bases include internal company documents (e.g., Confluence pages, wikis, or emails), product catalogs, customer support logs, and even specialized datasets like scientific papers or medical records.

The quality of a knowledge base is essential for the performance of AI systems — the data must be structured in a machine-readable format that captures the context and relationships within the data to ensure efficient retrieval. Ultimately, the effectiveness of an AI system depends on how well they can access and utilize the information in these knowledge bases.

2.3 Vectors

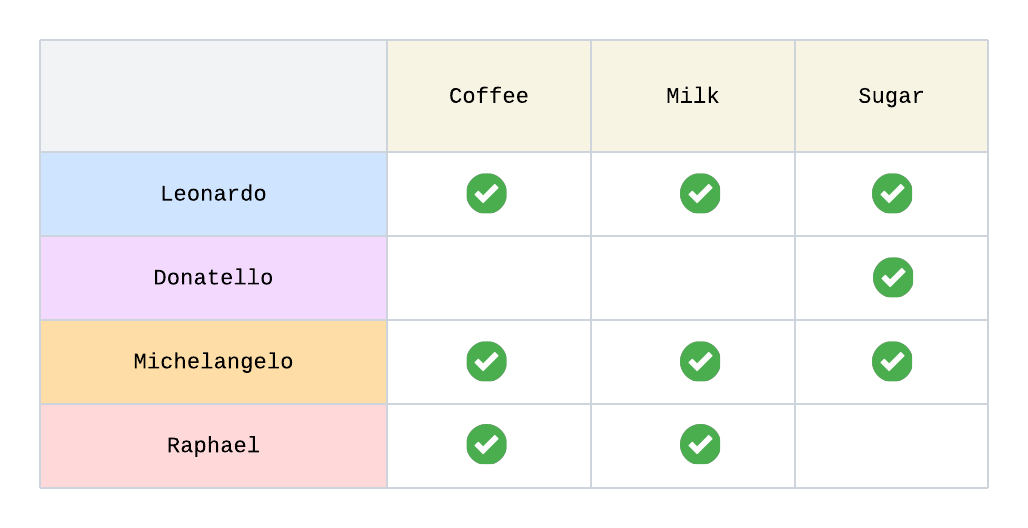

Consider an example of a recommendation engine:

To decide what product to recommend to a given customer, we could look into which products other customers purchased and see if there are other customers who have a similar purchase profile. For instance, both Leonardo and Michelangelo purchased coffee, milk, and sugar while Raphael has only purchased coffee and milk, so sugar may be a good recommendation for Raphael.

In this example, it is very easy to intuitively see that sugar should be recommended to Raphael without needing to do any calculations. But in reality, the complexity increases exponentially with more users, products, and relationships between all of the entities. There is a need for a more robust and objective way of representing these relationships, as well as techniques to find the most relevant data points from any given starting data set.

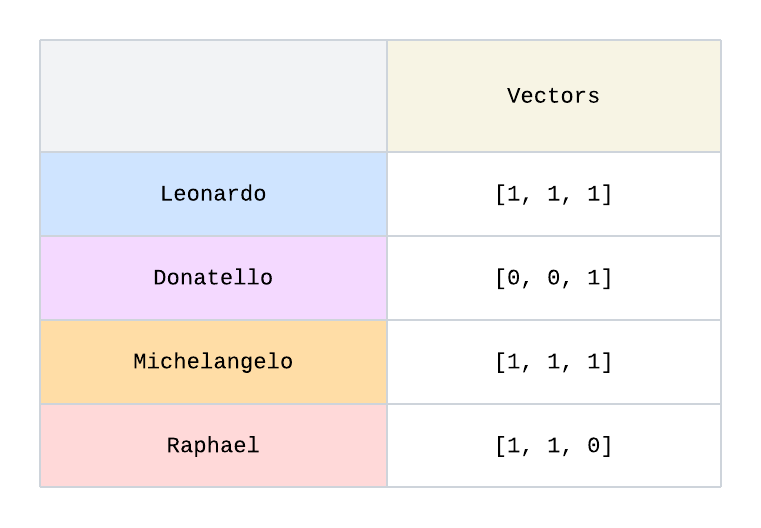

The relationships can be represented as shown where 0 corresponds to “not purchased” and 1 corresponds to “purchased”. These sets can be described as vectors:

Vectors are mathematical representations used to represent relationships, similarities, and patterns. In its most basic form, a vector is a list of numbers. We defined a purchase as a 1 and represented a customer’s purchase as a vector [1, 1, 1]. In the example given, there are three elements in the list so we can also think of the vector as a point in a 3-dimensional space. If we compare where Donatello and Raphael are in this 3-dimensional space, we can easily intuit that Raphael [1, 1, 0] is closer than Donatello [0, 0, 1] to the point [1, 1, 1] so Raphael has a purchase profile more similar to Leonardo and Michaelangelo and is thus more likely than Donatello to purchase sugar.

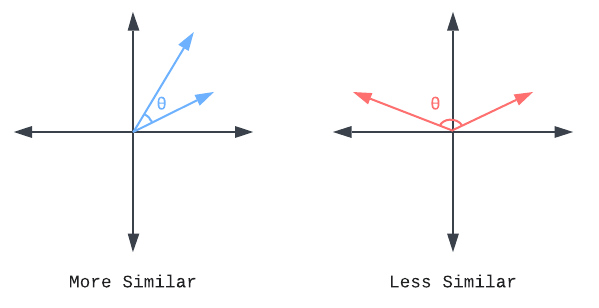

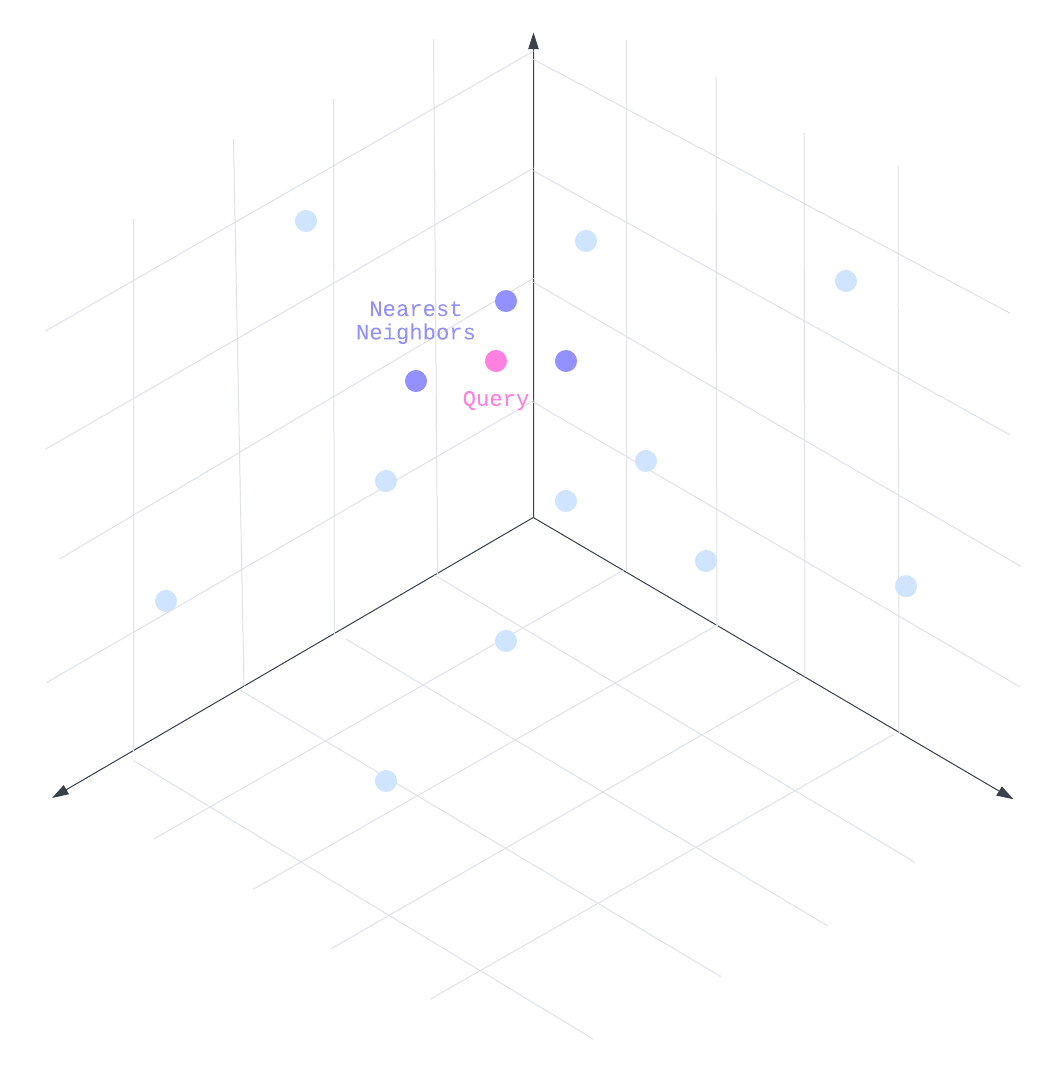

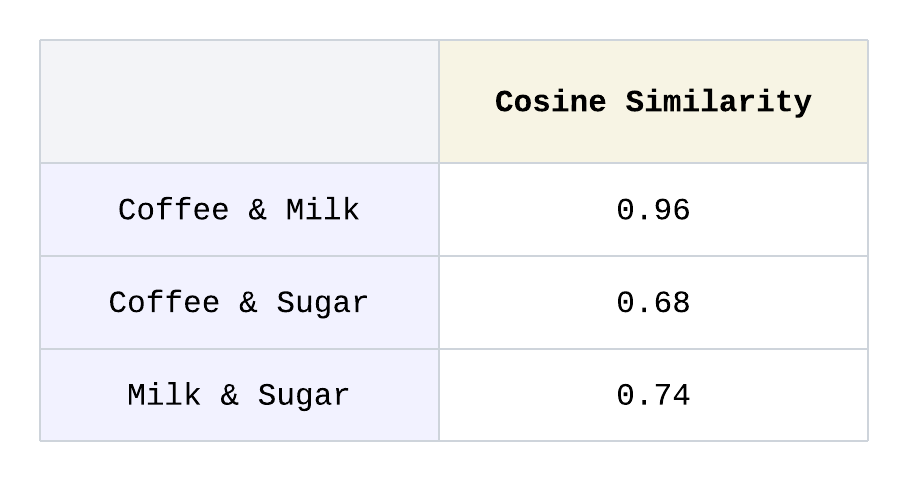

As the complexity and number of dimensions increases, it becomes more challenging to determine similarities or differences. One method of calculating similarity is cosine similarity, where the angle between two vectors is calculated. A smaller angle corresponds to a higher similarity. Through this method, given one customer’s vector representation of purchase history, we are able to determine which customer has the highest cosine similarity and therefore the customer with most similar purchase history. An algorithm called K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN) allows you to choose any number K and find the K most similar customers to a given data point, also known as the “top K” hits of the most similar vectors.

To be able to efficiently retrieve similar vectors, especially as the number of vectors increases, we must rely on specialized techniques. In our example, there are only 4 vectors, but knowledge bases typically have at least thousands of vectors and some even exceed millions of vectors. It becomes prohibitively expensive in time and resources to compute and compare vectors to all others to determine similarity. Instead, vector indexing algorithms optimize the retrieval process by using specialized data structures that organize vectors in a way that makes similarity searches more efficient. An example of an algorithm is Approximate Nearest Neighbors (ANN) where vectors are not directly compared but utilize specialized data structures to give approximations of which vectors are close to each other, trading minor accuracy loss for significantly improved retrieval times. The use of these types of algorithms makes it possible to query and retrieve vectors even in large datasets.

Revisiting the products example, we used an intentionally oversimplified manner of transforming a user’s purchase history into vectors by a simple mapping of products to either 0 or 1. In practice, representing data as vectors must be done systematically and in a way such that the resulting vectors are accurate representations of the underlying data to begin with. Such vectors are known as embeddings.

2.4 Embeddings

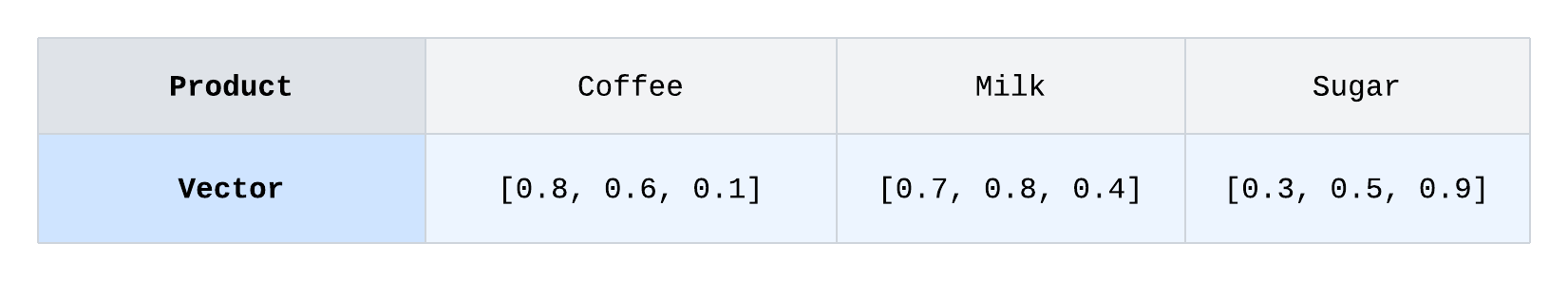

An embedding is a type of vector that represents data in a more efficient way by being low-dimensional and dense. Unlike traditional vectors, which can have a high number of dimensions and mostly contain zeros, embeddings aim to reduce the number of dimensions while still capturing the most important features of the data. We presented an example where a vector represents a purchase or non-purchase of an item for illustrative purposes, but if we expand this to a wide catalog of products, we expect that most of the elements in the list will be empty and the list would be mostly filled with 0’s, making the list “sparse”. Such vectors are inefficient because they have many empty elements and don't effectively capture relationships between different items. For example, coffee is equally “distant” from milk and sugar because they are both 1 unit away in that dimension. In reality, we can reason that coffee is more closely related to milk as they are both drinks, associated with breakfast, and are frequently consumed both hot and cold. The closeness of coffee and milk versus coffee and sugar is not adequately represented in the simple vector representation of 0’s and 1’s. Embeddings are used instead to map this sparse information into a smaller, more compact vector with non-zero values. A large, sparse vector like [1, 0, 0, …, 0] is represented as a smaller set of “dense” values, such as [0.34, -0.84, 0.15], which makes embeddings far more efficient and better at reflecting meaningful relationships and their true connections.

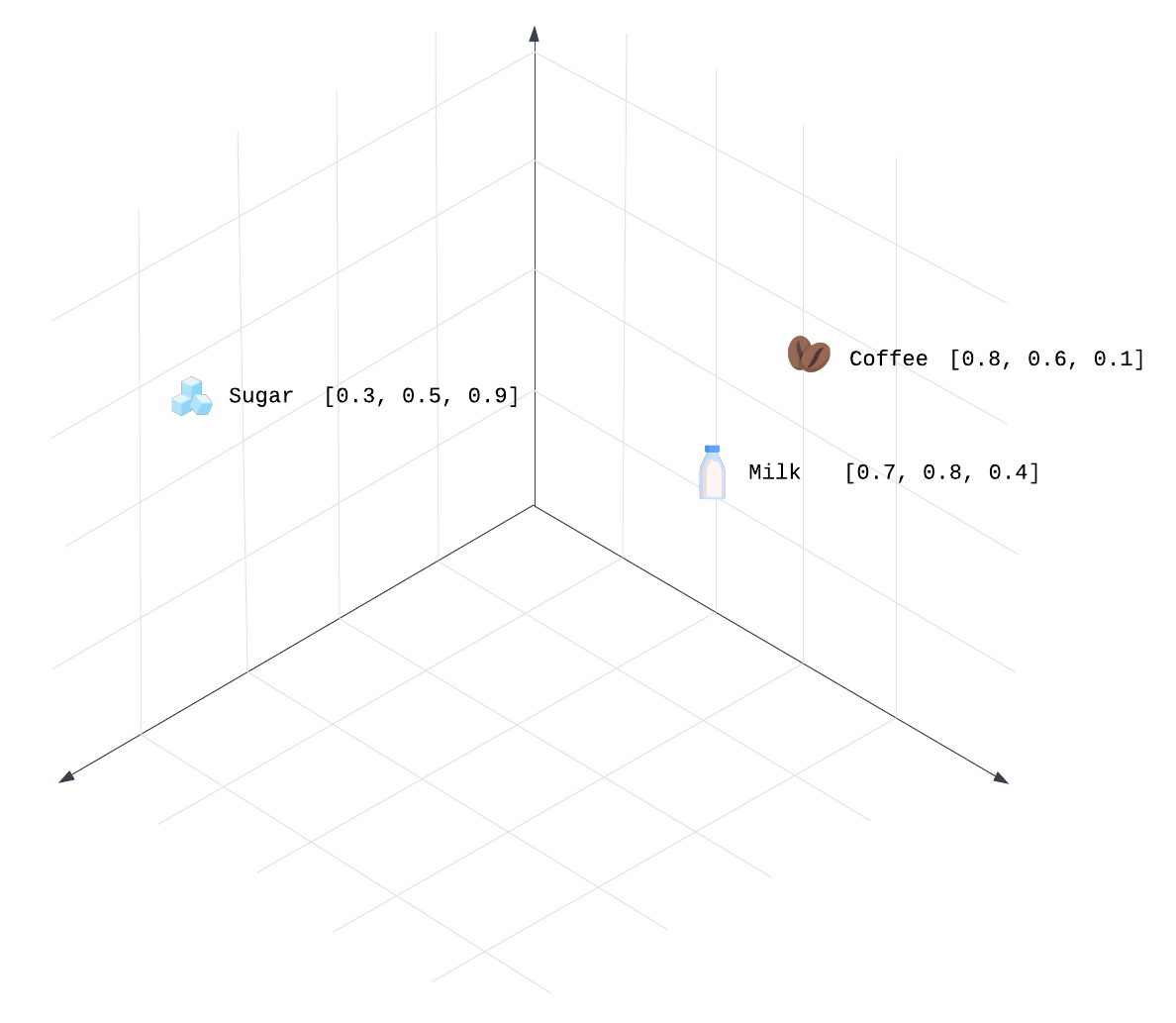

Here, the vectors for coffee and milk are the closest in 3-dimensional space based on cosine similarity.

The first two values ([0.8, 0.6] for coffee and [0.7, 0.8] for milk) likely represent contextual features or characteristics such as being drinks or associated with breakfast. These two products have strong similarities in how they are commonly consumed together. The first two values for sugar [0.3, 0.5] are less similar because sugar has a weaker association with drinks or breakfast items, although still has some involvement in many food contexts. The last value (0.1 for coffee, 0.4 for milk, and 0.9 for sugar) may reflect their broader use in food preparation, such as in baking recipes, where both milk and sugar are frequently used in sweet dishes, while coffee tends to be less common. This difference in how these products are typically used in recipes helps explain why sugar is more closely related to milk than to coffee.

In a more real-world application of our products example, an embedding may represent not only a customer’s purchase history but also a customer’s personal information, more specific product details, or a customer’s interactions on an e-commerce site. Here we can imagine that a recommendation engine could recommend sugar because it has been a few months since Raphael has purchased sugar and his local supermarket has a sale on organic sugar which he may prefer because he has also purchased organic foods in the past. This recommendation is based on the relationship intersection of all of the vectors that represent Raphael.

Overall, representing data as vector embeddings aims to capture the more nuanced relationship and structure in the data. It is also important to note that embeddings are not limited to data that you might see in recommendation engines. Text, images, and numbers are among common data types that are represented by embeddings which all require different strategies to transform data and generate embeddings.

Embeddings provide a powerful means of representing data in a structured, machine-readable format. However, leveraging embeddings at scale requires systematic data pipelines to transform raw data into these usable representations. This transformation is critical for preserving the underlying relationships and context of the data, ensuring that embeddings can be effectively applied in downstream AI tasks.

2.5 Data Pipelines: Traditional ETLs

The process of handling data by moving it through various stages of transformation and preparing it for final use is often achieved through a data pipeline. A pipeline can be thought of as a sequence of steps that the data flows through, from raw input to structured output, like liquid flowing through a pipe. Each stage in the pipeline performs a specific task, transforming the data in some way until it reaches its final, usable form.

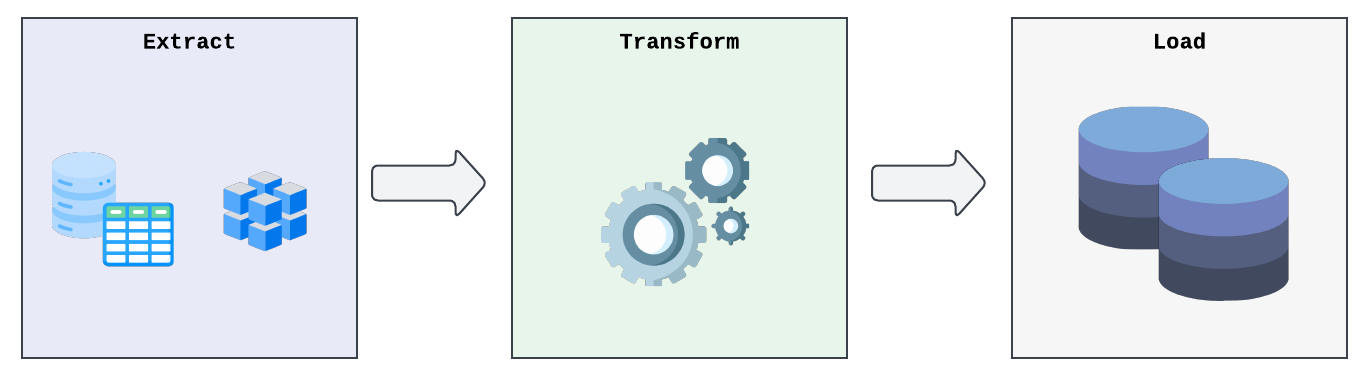

A common type of pipeline is ETL which is comprised of Extract, Transform, and Load steps:

- Extraction refers to the collection of raw data from different sources such as documents. The steps necessary to extract information differ in implementation depending on the types and formats of the given file (eg. PDF, CSV, JSON, etc.).

- Transformation involves parsing information out of the raw data and performing operations such as cleaning and removing unnecessary items, enrichment or operations on the data, or normalizing the data to make it suitable for use.

- Loading the data completes the pipeline by sending the transformed data to storage such as a database for further applications. The loading step can also include managing the flow of data to prevent spikes, monitoring for errors, or database indexing to assist in future processing steps.

The success of a pipeline’s output is determined by the quality of data and its accuracy and consistency from start to finish. Transforming data – specifically to vector embeddings – using a traditional data pipeline introduces additional challenges that require specialized techniques in order to properly retain the semantic meaning, context, and relationships between data points, all of which are required for AI applications to function.

2.6 Data Pipelines: AI-Focused ETLs

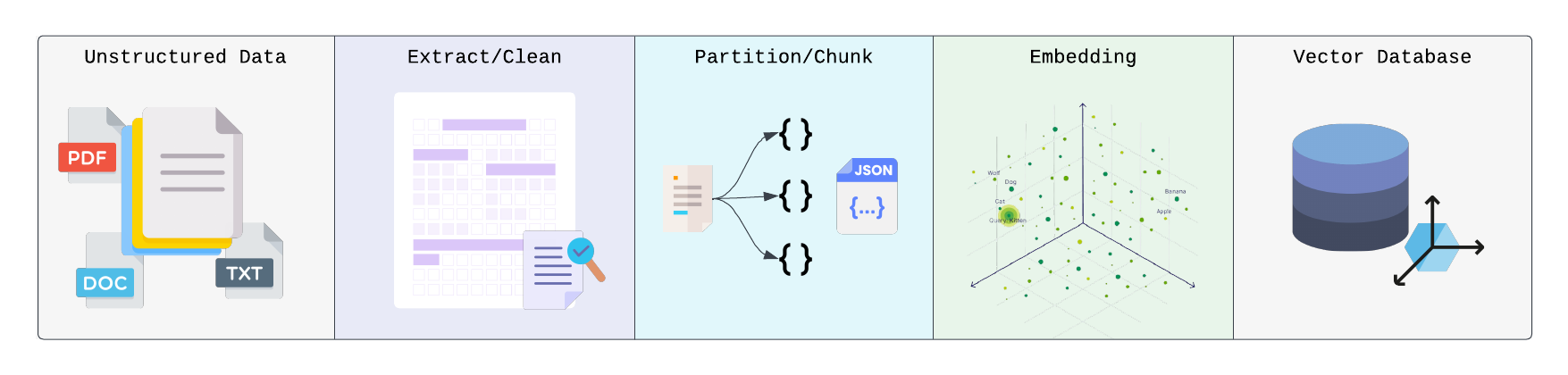

In AI applications, effectively preparing and structuring raw data is essential for enabling models to extract meaningful insights. Before AI can process text or other data, it must first be broken down into smaller, more manageable pieces through partitioning, chunking, and embedding. These preprocessing steps ensure the data is organized in a way that preserves its semantic structure, allowing AI models to better understand relationships, context, and meaning. This foundational work is crucial for AI systems to generate accurate and context-aware results.

Partitioning and Chunking:

Partitioning describes the breaking of raw data into smaller elements, which can be units that logically fit together based on their semantically meaningful context. Partitioning also pairs with chunking where groups of data are intelligently categorized based on a logical and contextual boundary. For instance, in a text document, we expect the contents of a paragraph to group together rather than an arbitrary designation that each set of 500 characters should form a group. In addition, the chunking step retains hierarchical information. For example, chunks can correspond to a title, subtitle, and body, and the “title” chunk might have an overarching relation to all of the “body” chunks in its section.

Embedding:

After these steps, chunks are ready to be converted into a vector representation through the use of an embedding model. Embedding models are a type of machine learning model that has the ultimate goal of transforming input data into vectors that capture the semantic meaning and relationships between data points. Different embedding models may have different implementation, architecture, and result in vectors with different dimensions, but generally share the same underlying principles.There are many options for embedding models like OpenAI’s “text-embedding-ada-002” which is a proprietary model or an open-source model such as “BAAI/bge-base-en-v1.5” found on HuggingFace.

During embedding, data sent to the embedding model is preprocessed with a tokenization step which splits data into smaller units called tokens. For example, text may be split into words or even individual characters. These tokens are converted to a dense vector representation based on pre-trained embeddings from the vocabulary of the training data that was used for the model’s training. Pre-trained embeddings capture the semantic information about a word and its context based on the library of information that was used in the model’s training. The model will also determine the relationship between words even if they are far from each other. In the sentence “the student stirred her coffee”, the model can help understand how “student” relates to “stirred” and how “coffee” relates to the context of “stirred” to determine the weight of each word in relation to every other word. The output from these steps is a set of contextual embeddings for each token which represents the relationship to other tokens. From these embeddings, the model may either aggregate the information to represent the full chunk as a vector or keep token-level embeddings.

Overall, the embedding step is an important part of the pipeline as it prepares the data to be usable for downstream tasks but also depends heavily on the previous steps. If data was properly extracted, cleaned, partitioned, and chunked, we can be confident that the resulting vectors will faithfully represent the underlying data.

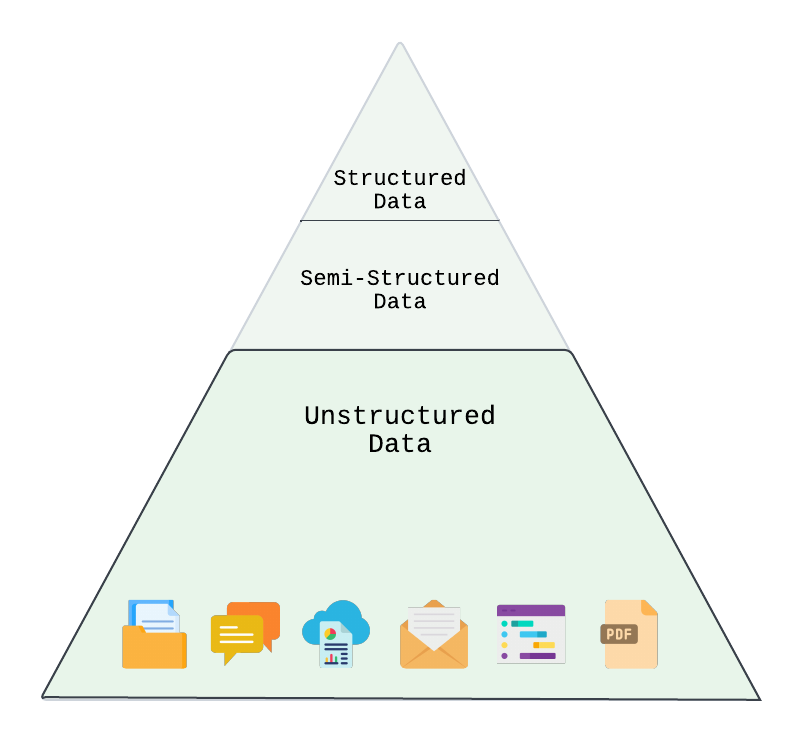

2.7 Unstructured Data

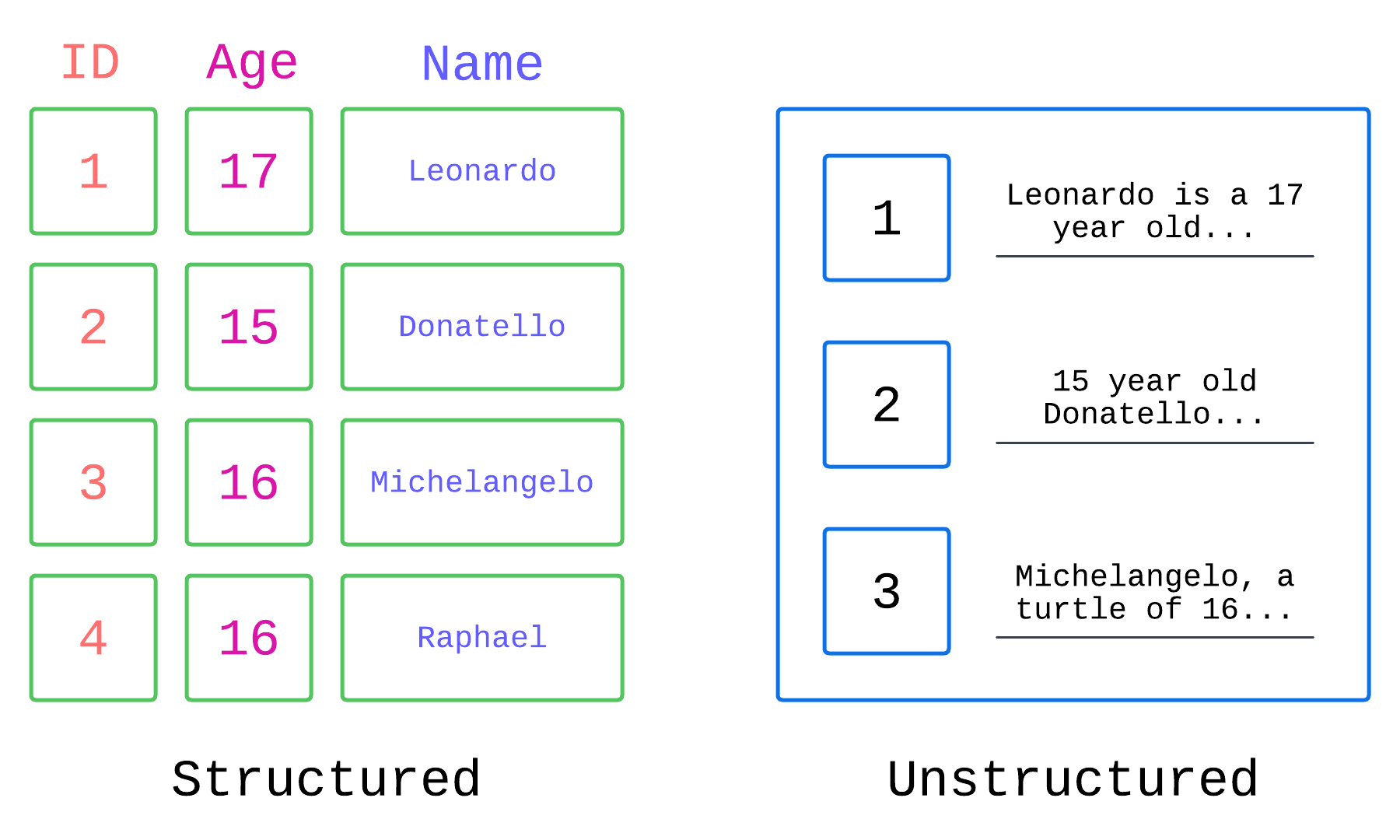

While traditional data pipelines may focus on structured data (eg. relational tables, spreadsheets), there is a wealth of data that exists as unstructured data. This type of data does not follow a predictable schema but can be immensely rich in data, especially data that is useful for AI applications. Fortunately, data pipelines that perform tasks such as partitioning, chunking, and embedding are particularly relevant for unstructured data as they assist in converting the complex, raw data into the structured and meaningful embeddings that AI models can use and understand.

When we work with structured data, we work with data that is highly organized and has a predictable schema. Examples of structured data may be a relational table with customer names, emails, and phone numbers, which in turn might have a relationship to another table that stores information about orders, such as the date of a sale, products, and which customer placed the order. The relationship between the entities is well-defined and predictable, making it more straightforward, for example, to pose a query retrieving information by asking what was the most recent order by a customer named April O’Neil. Structured data types also tend to integrate well with other tools given their organization and predictability.

However, while structured data is easier to work with, it’s estimated that 80% of data is unstructured. This includes emails, Slack messages, blog posts, training videos, or customer support chats, all of which contain valuable information in a loose structure, but are often scattered across various locations. Additionally, industries like healthcare and law deal with highly regulated data, such as medical records or court transcriptions, which also require careful handling. Organizations may also have proprietary data, like training manuals or internal notes, that are essential but difficult to manage. Some industries have strict regulations that require tighter control over where data is stored and processed to ensure compliance with privacy laws and standards. Frequently, unstructured data sources contain highly valuable and useful information but can be the most difficult to work with. Extracting the information from this data requires more specialized techniques such as natural language processing or computer vision.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) aims to enable machines to understand and interpret human language and is important when dealing with text-based unstructured data. NLP techniques include text preprocessing such as tokenization, seen in embedding models. NLP also includes general classification of text such as sentiment analysis which seeks to determine if text has a positive, negative, or neutral tone. Another aspect of NLP is recognition of entities. A section of text such as “Shredder threw the pizza in the sewer yesterday” is parsed to distinguish each word as either a person, item, location, time, etc.

- Computer Vision (CV) enables machines to understand and interpret visual information and is important when dealing with image-based unstructured data. CV techniques can include classification and detection of objects in an image, such as identifying the difference between a car from a truck and also identifying all of the different cars in a parking lot. One CV technique that is also useful for text-based data is Optical Character Recognition (OCR) where the detection of characters is accomplished through pattern recognition and can transform an image of text into its raw characters and words.

These techniques are some examples of how machines can help with identifying the overall meaning of data and allow these systems to better determine the contextual relationships between elements in unstructured data.

We have seen how unstructured data requires a more sophisticated data pipeline that includes intelligently executed partitioning, chunking, and embedding to fully extract meaningful insights from data sets. Data pipelines play a critical role when processing unstructured data and are crucial to transform raw data into vectors that accurately and faithfully capture the meaning behind the content. These embeddings are then able to support and drive downstream use, produce highly relevant and accurate outputs, and unlock the greatest potential out of AI-driven applications.

3. Challenges in the Domain

3.1 Existing Solutions

To meet the demand for working with unstructured data in modern AI applications, tools like Vectorize and Unstructured.io have emerged, offering powerful solutions for processing unstructured data at scale. These tools are designed to manage the complexity of unstructured data while preserving its rich context and meaning.

Unstructured.io simplifies the preprocessing phase by extracting raw data from diverse formats such as PDFs, images, emails, and videos. Leveraging techniques like partitioning, chunking, and Optical Character Recognition (OCR), it allows developers to easily break down data into manageable components without losing contextual relationships.

Vectorize, on the other hand, specializes in transforming data into embeddings. By converting text, images, and other data into numerical vectors, Vectorize enables unstructured data to be used effectively in AI systems.

Tools like Unstructured.io and Vectorize streamline the process of turning raw, unstructured data into actionable insights. Specialized to address the unique challenges of unstructured data, these solutions help overcome some of the limitations of traditional ETL processes.

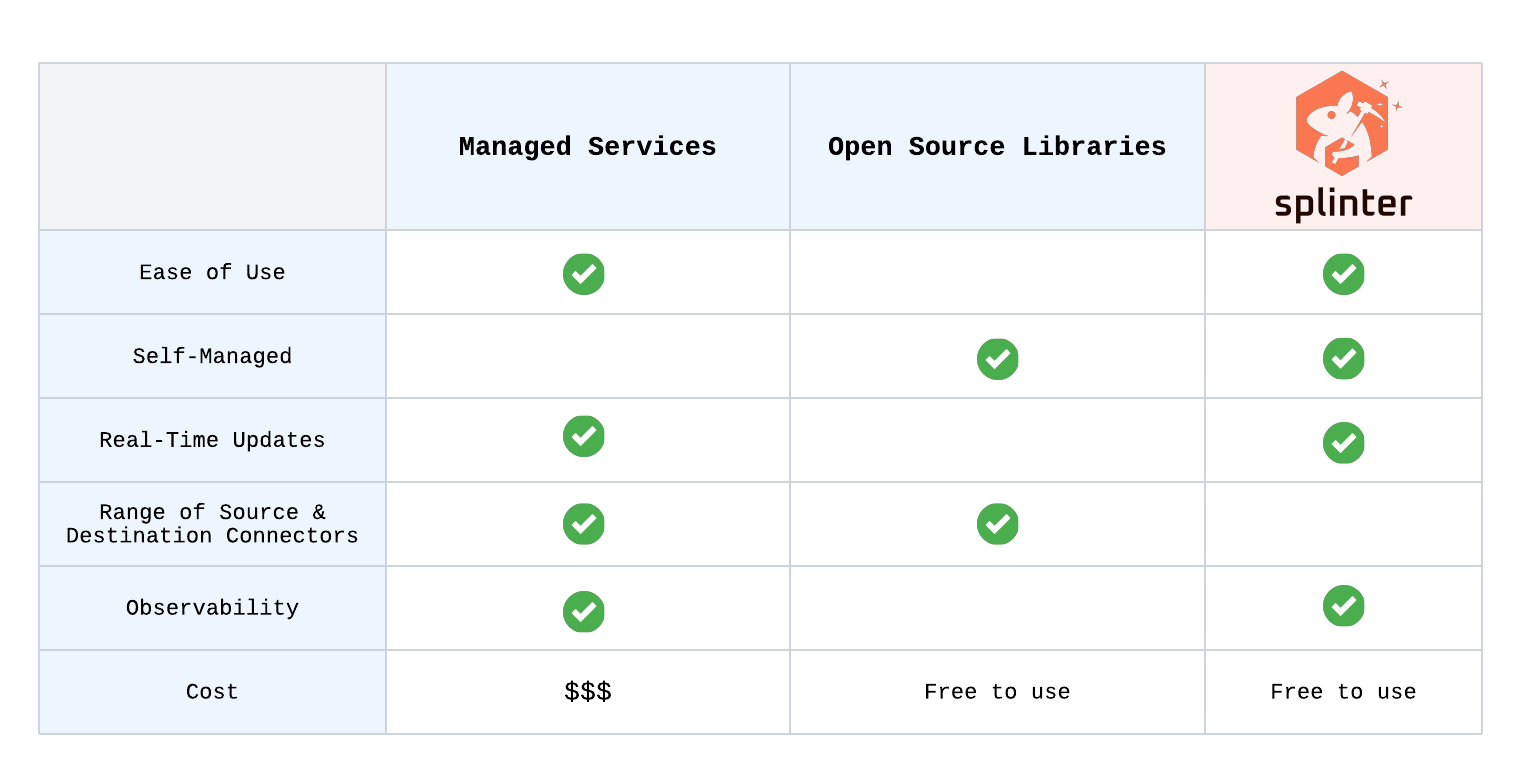

Tradeoffs

Both Unstructured.io and Vectorize provide a wide range of source and destination connectors, robust infrastructure, and user-friendly interfaces tailored for large enterprise solutions. However, these platforms are managed by their respective companies, which limits user control over pipeline configurations. Additionally, users must entrust their internal data to third-party management—an option that may not appeal to users who prefer self-managed pipelines.

Unstructured.io also offers an open-source library with a limited scope compared to their hosted solution. This open-source option provides a degree of flexibility for users willing to handle setup and integration themselves. However, the process can be complex, making it less approachable for users without significant technical expertise. Vectorize does not provide any open-source solutions, leaving users reliant on their managed platform.

Recognizing that some users require enhanced control over their data, particularly in terms of privacy and security, we developed Splinter as an alternative solution. Splinter allows users to deploy the application within their own AWS account, ensuring that all data processing remains internal and fully under their control. The self-managed deployment not only provides greater flexibility, but also ensures that sensitive data is kept private. This gives users the autonomy to configure and customize their pipelines while maintaining robust data privacy.

3.2 Introducing Splinter

Splinter is a self-managed, serverless pipeline designed to simplify the processing of unstructured data and its integration into knowledge bases.

Self-Managed

Splinter is fully built using AWS architecture, meaning developers only need an active AWS account to deploy the pipeline. Splinter’s self-managed, serverless design makes it especially useful for organizations seeking both scalability and control over their unstructured data pipelines.

Example Use Case:

A research organization needs to process unstructured documents containing historical data, scientific articles, and datasets. By deploying Splinter in their AWS environment, they can configure the pipeline to process sensitive data securely within their own cloud environment. The serverless design ensures scalability during peak data ingestion periods, such as data migrations, without requiring constant resource management. This allows the organization to focus on deriving insights from the data rather than maintaining the pipeline.

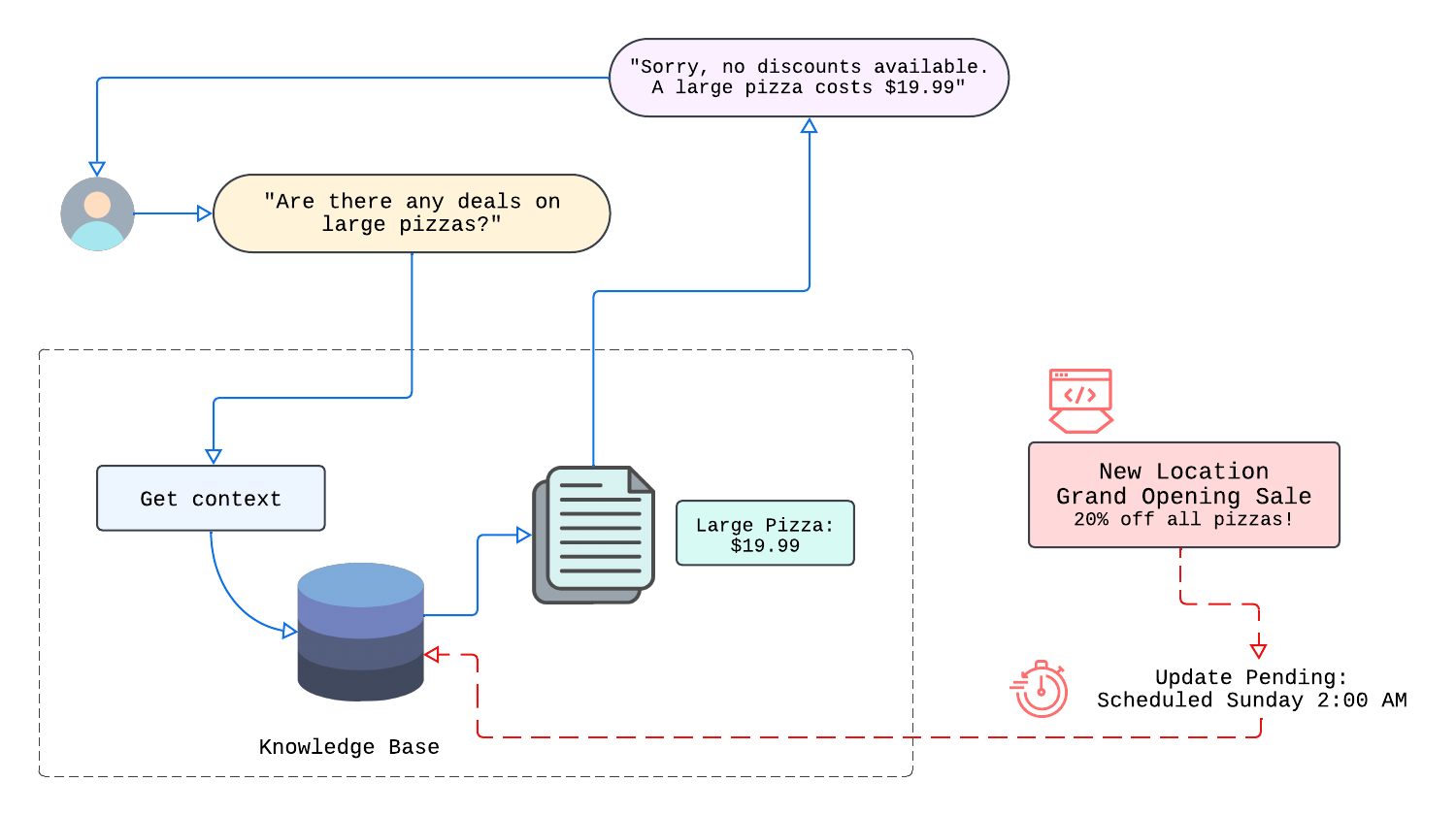

Avoiding Stale Data

A common challenge for knowledge bases is dealing with stale data—information that becomes outdated or irrelevant.

In many organizations, data is constantly changing. New documents are introduced, existing ones are revised, and irrelevant content is removed. Without a strategy to keep the knowledge base and its associated embeddings synchronized, the system will inevitably lag behind current information, leading to less accurate answers and reducing user trust.

To stay reliable, both the documents and also the vector embeddings in a knowledge base need to be continuously refreshed. By doing so, the overall system keeps pace with new, revised, or removed content, ensuring users always see up-to-date information.

Splinter solves this by synchronizing data sources like AWS S3 or Dropbox with the destination database, automatically updating whenever documents are added, updated, or removed. This ensures the knowledge base reflects the latest data, reducing errors and enhancing relevance.

Example Use Case:

An independent online store uses Splinter to synchronize product catalogs stored in a AWS S3 bucket with a vector database like Pinecone. When the store owner updates product descriptions, Splinter ensures the changes are immediately reflected in the knowledge base, preventing outdated information from affecting customer search results and improving the overall user experience.

Ephemeral and Event-Driven Design

Splinter’s ephemeral, event-driven design ensures that it "scales to zero," eliminating costs for idle compute resources. Its infrastructure components remain dormant until ingestion is required, triggering operations only when needed. This approach minimizes operational overhead and allows seamless scaling with demand, making Splinter a cost-efficient and flexible solution for dynamic workloads.

CLI Tool, Observability Dashboard, and RAG Sandbox

Splinter includes a Command Line Interface (CLI) tool to simplify pipeline deployment, making it easily accessible for developers.

Once the pipeline is fully deployed, a locally deployed user interface provides the following features:

Observability Dashboard

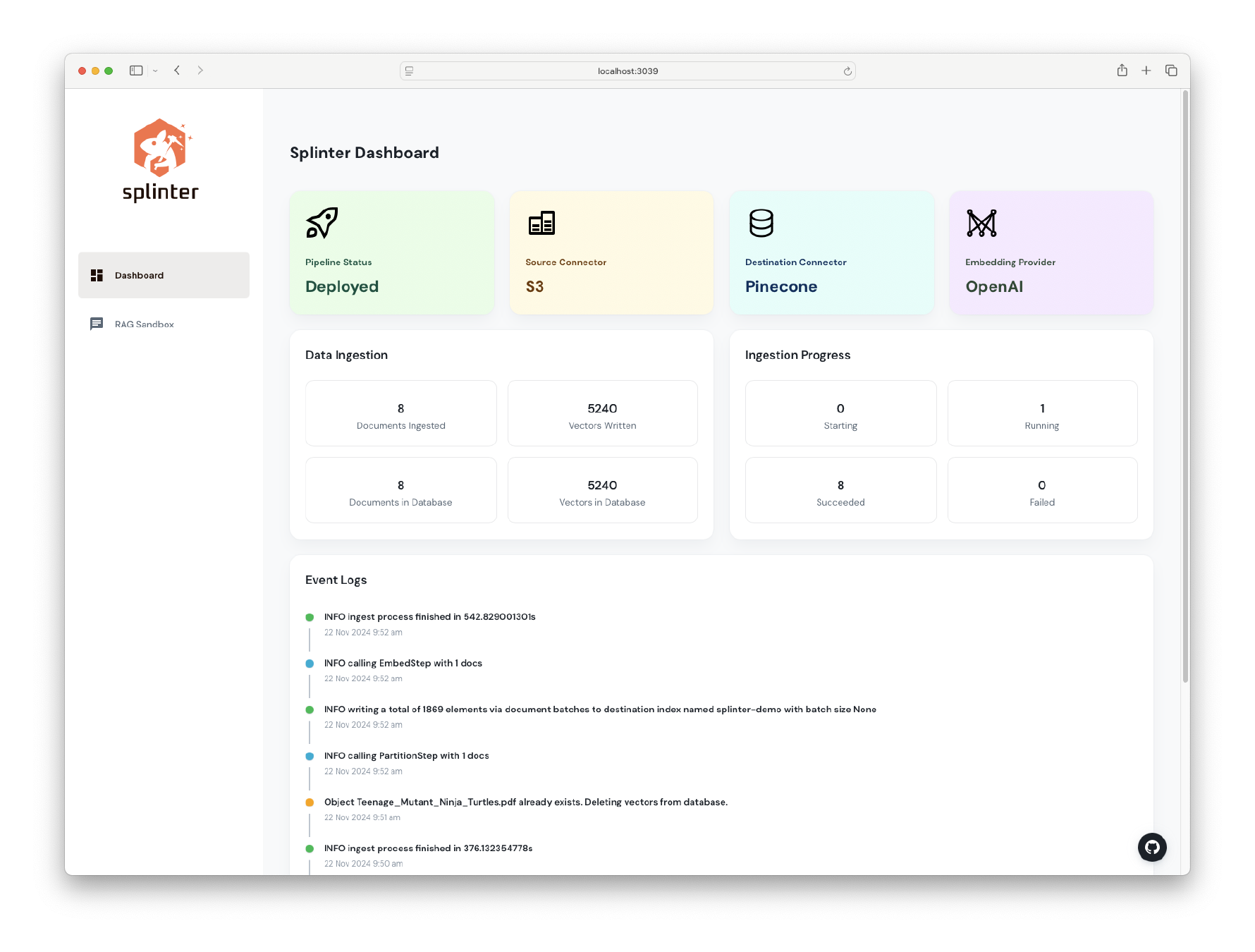

The dashboard offers real-time updates during the ingestion process, including the current state of each document’s ingestion, the number of existing vectors, and the number of new vectors added to the knowledge base.

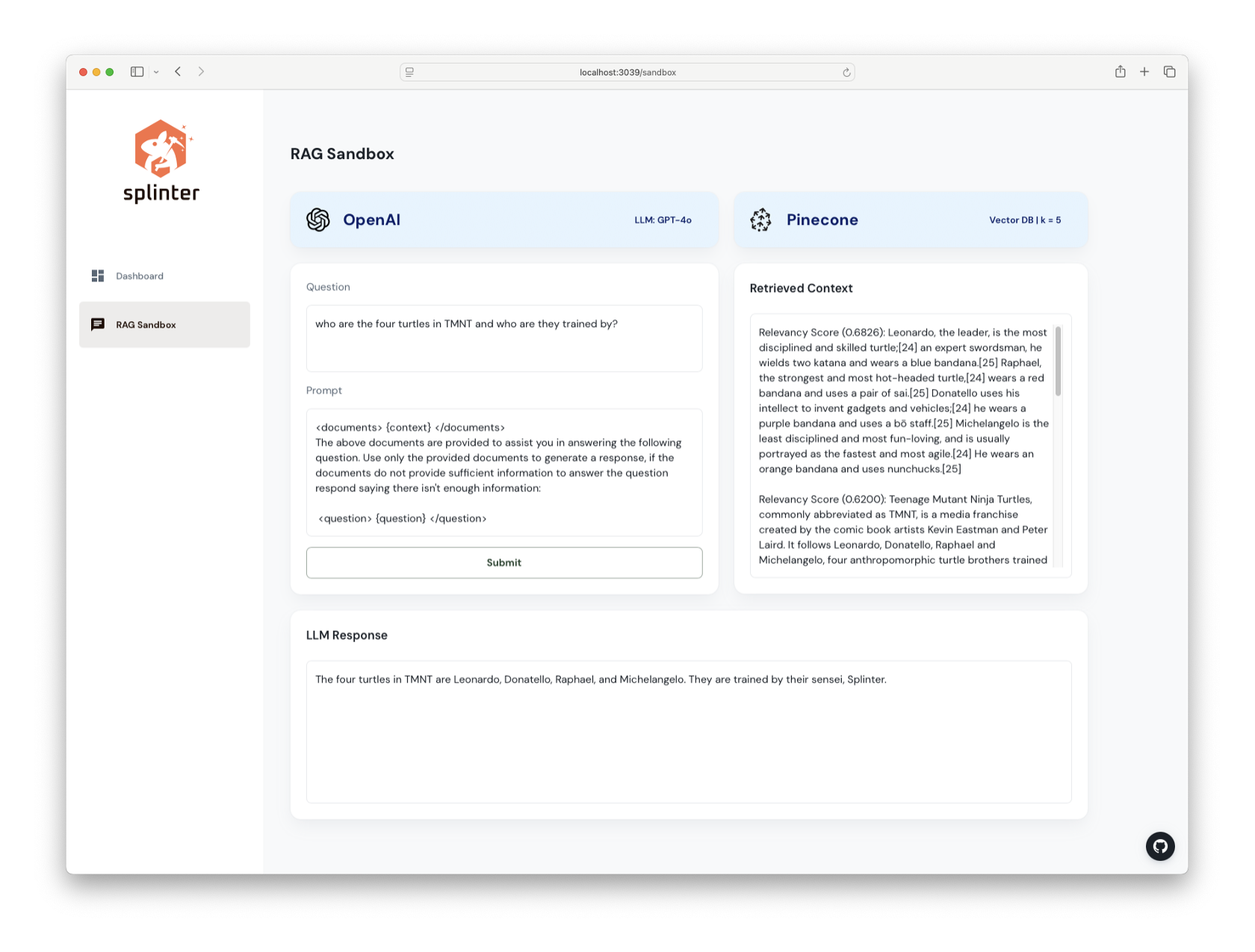

RAG Sandbox

The built-in RAG system uses the user’s destination database as its knowledge base. It updates its context based on the documents in the knowledge base, allowing users to verify the accuracy of the ingested data through direct queries.

Tailored for Focused Workflows and Smaller Teams

Splinter is intentionally designed to cater to specific use cases, particularly for teams handling lower volumes of document ingestion. While it offers a more focused selection of source and destination connectors compared to some enterprise-scale solutions, this deliberate scope makes Splinter an excellent fit for smaller developer teams or organizations with targeted workflows. Unlike fully managed platforms, Splinter is open source and self-manageable, empowering users with full control over their data and pipeline configurations. This approach ensures flexibility and privacy, making Splinter ideal for those whose needs align with its streamlined and developer-friendly offerings.

4. Demo / Walkthrough

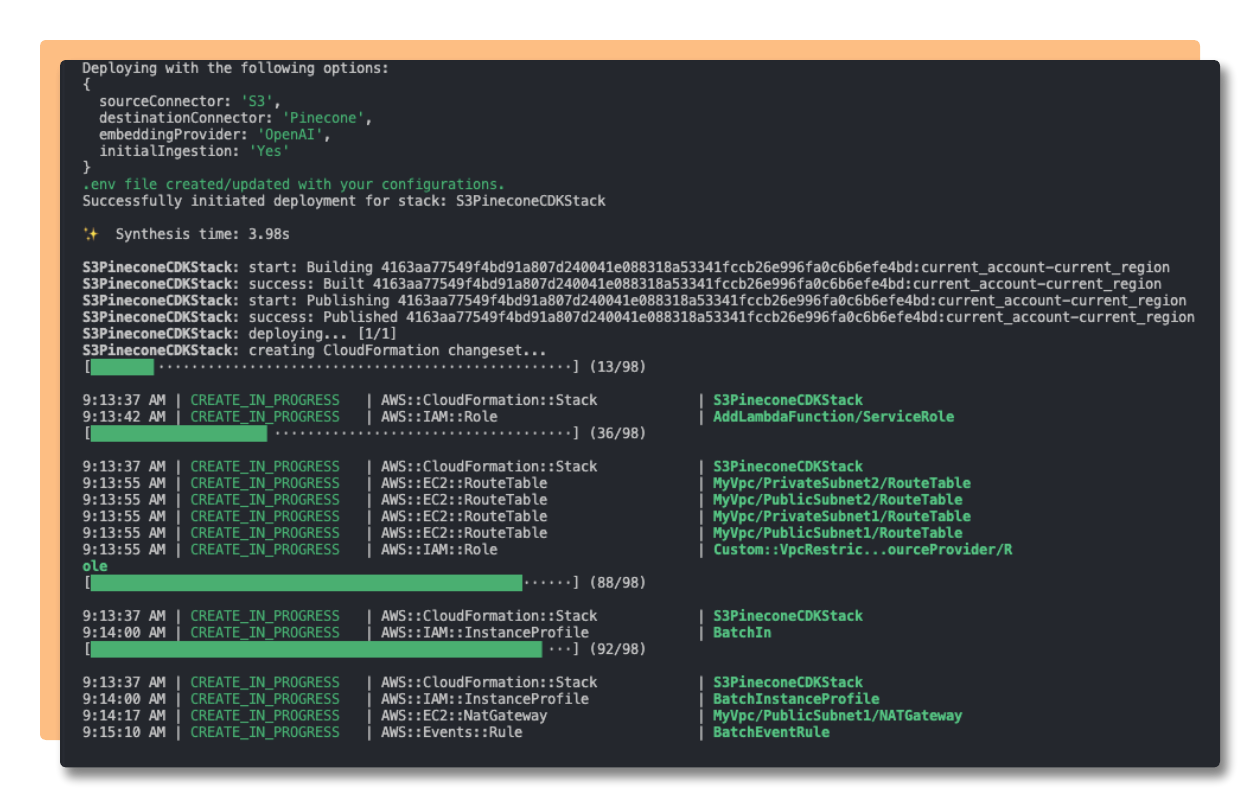

Splinter offers a Command Line Interface tool to walk the user through the initial deployment steps

After the selected options and configurations are set, the infrastructure is deployed using AWS Cloud Development Kit (CDK).

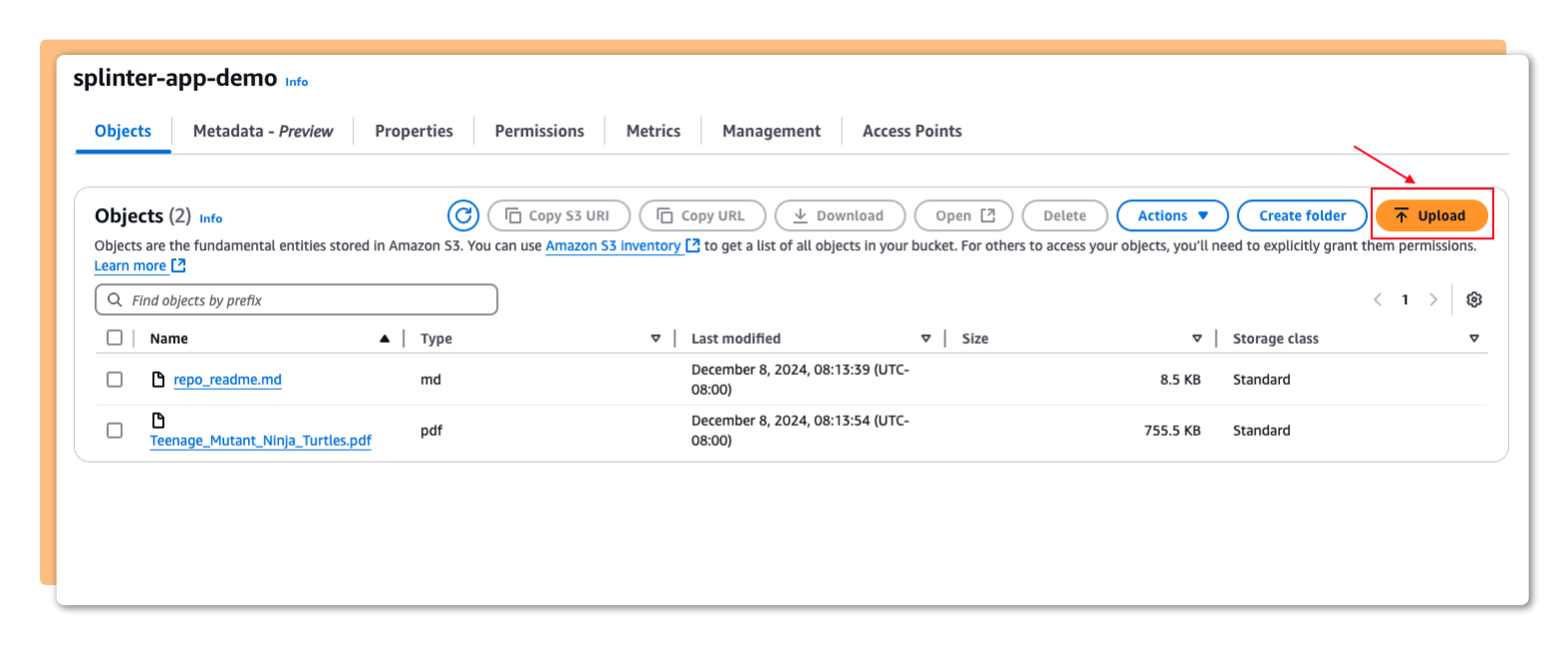

Adding, deleting, or updating files in the source triggers the appropriate action in the pipeline and database

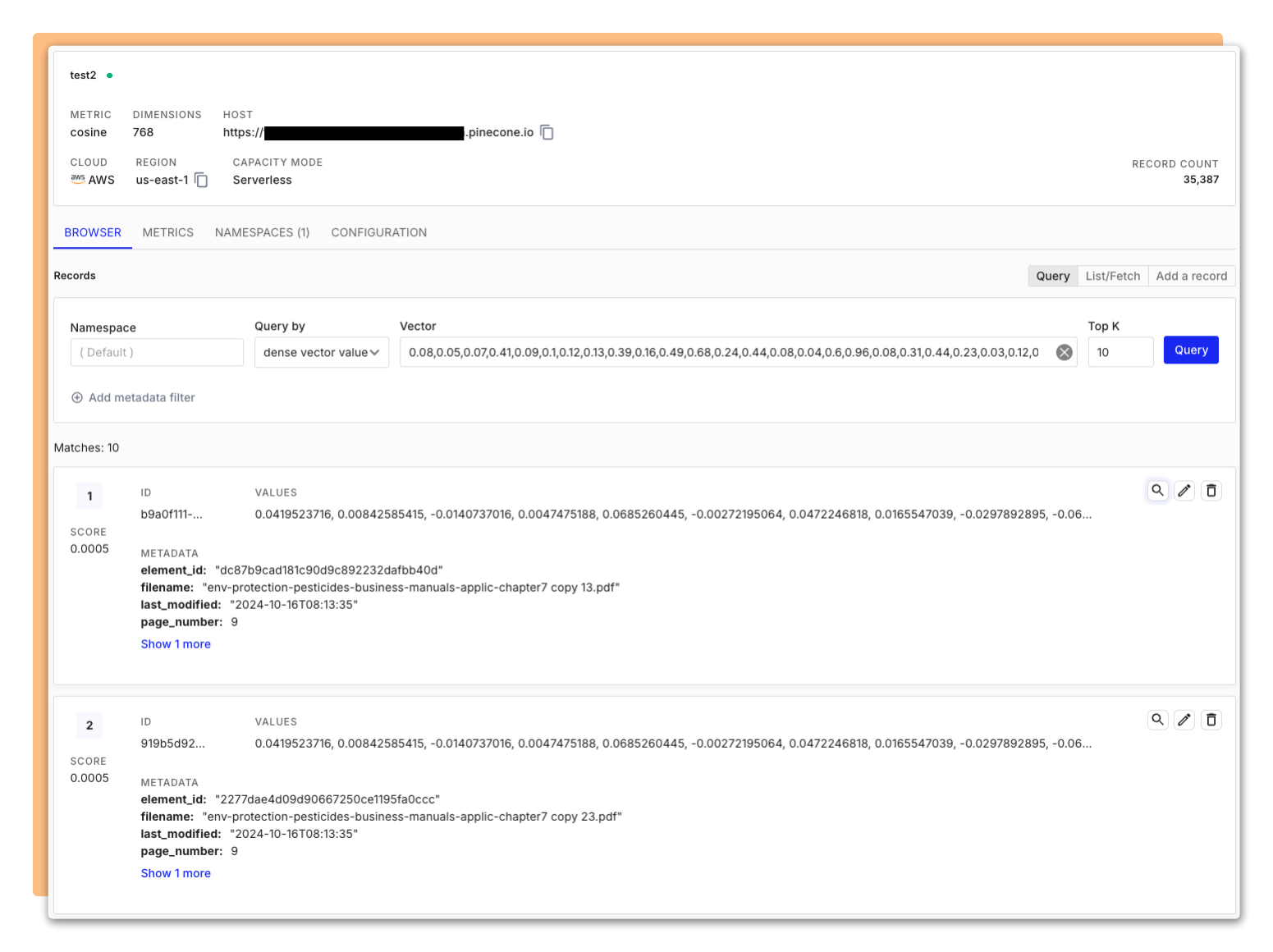

Vector embeddings are generated from the ingested document.

The observability dashboard displays information about the current progress and other metrics of the ingestion pipeline

The RAG Sandbox allows users to validate the vectorized data as a knowledge base. Users input a question and relevant context is retrieved to be used to generate a response from an LLM.

5. Architecture, Trade-offs and Challenges

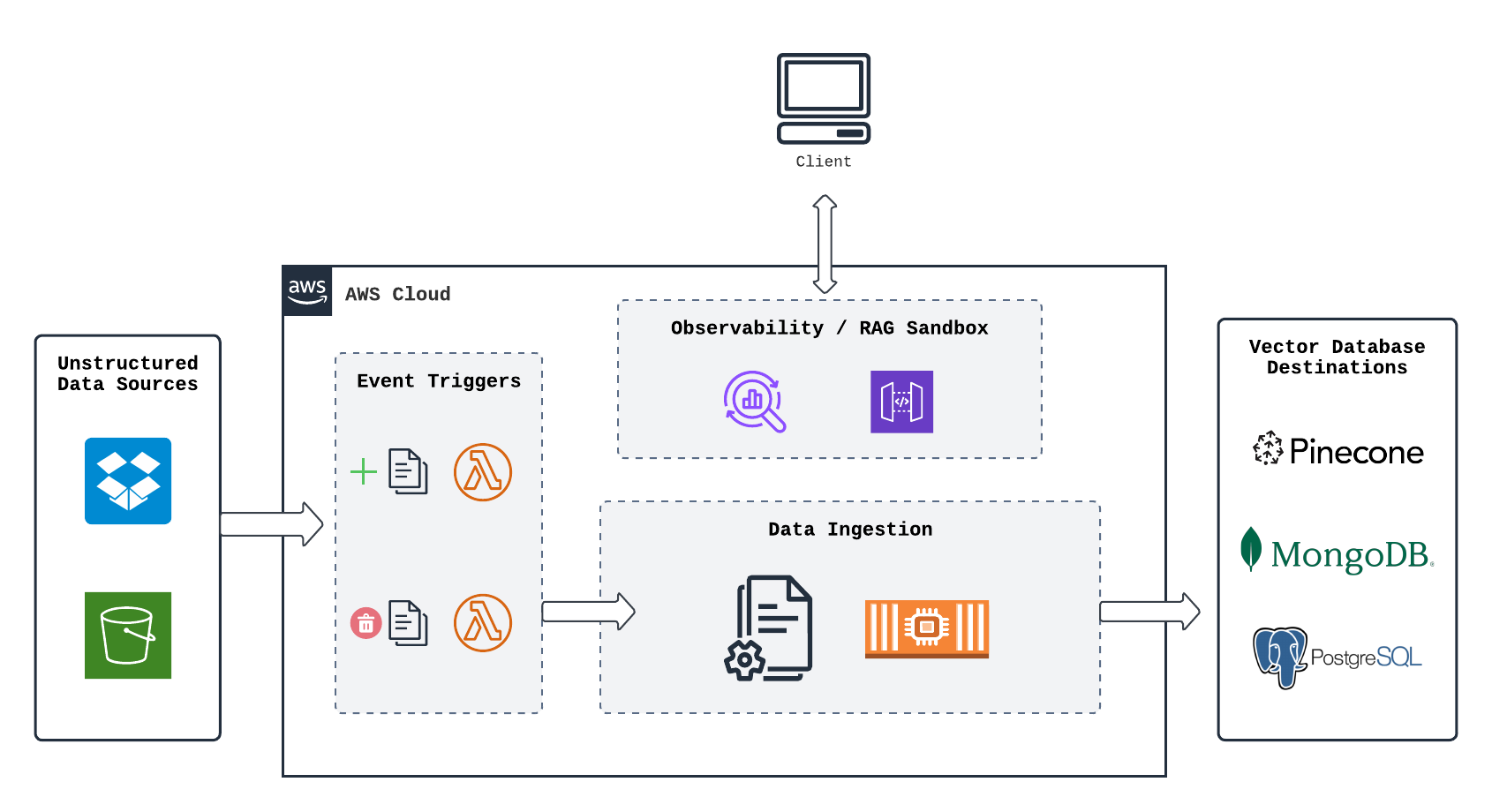

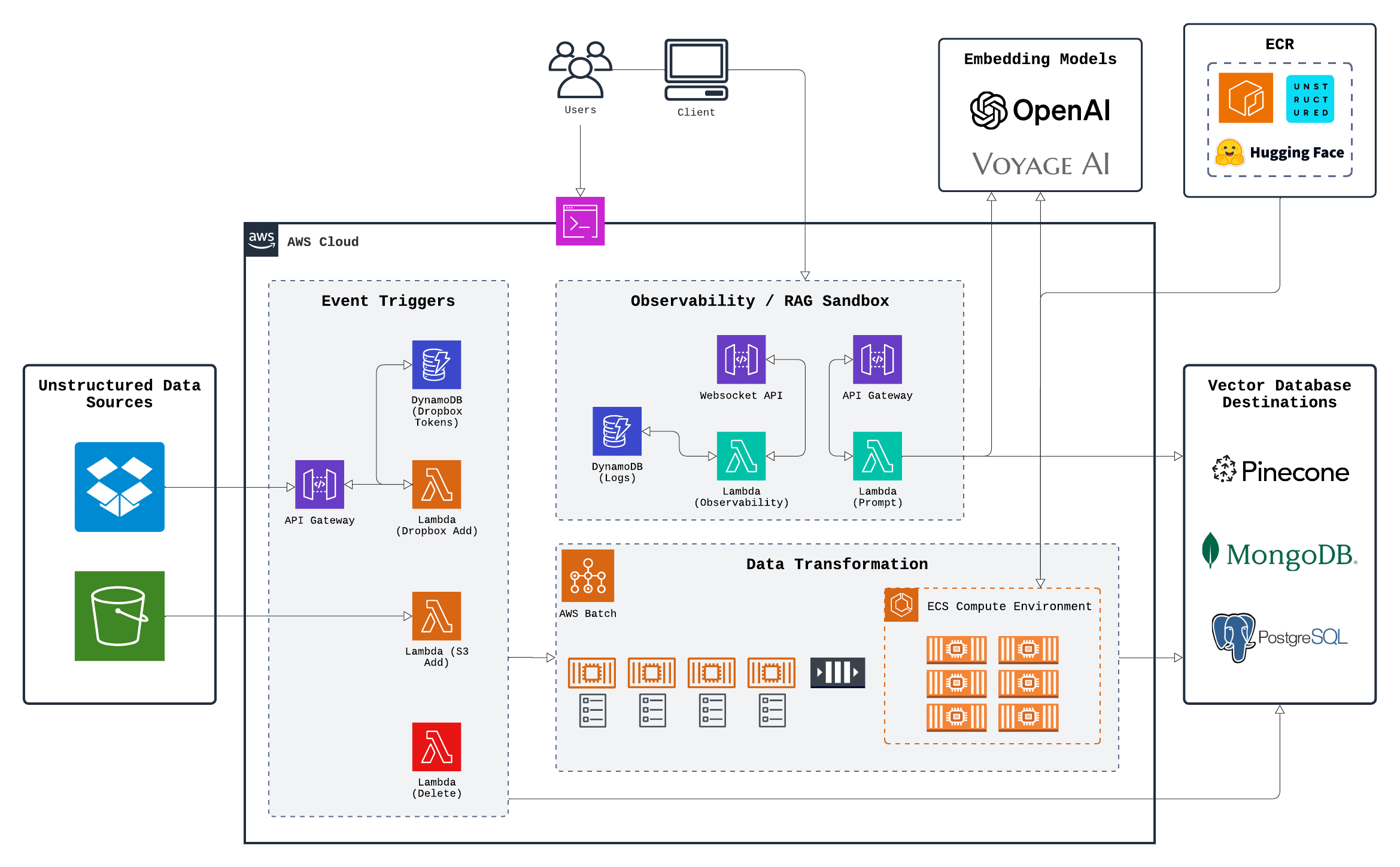

Splinter consists of 4 major subsections:

- Source (Data Sources and Event Triggers)

- Data Ingestion Engine

- Vector Database Destinations

- User Interface (Observability / RAG Sandbox)

5.1 Source

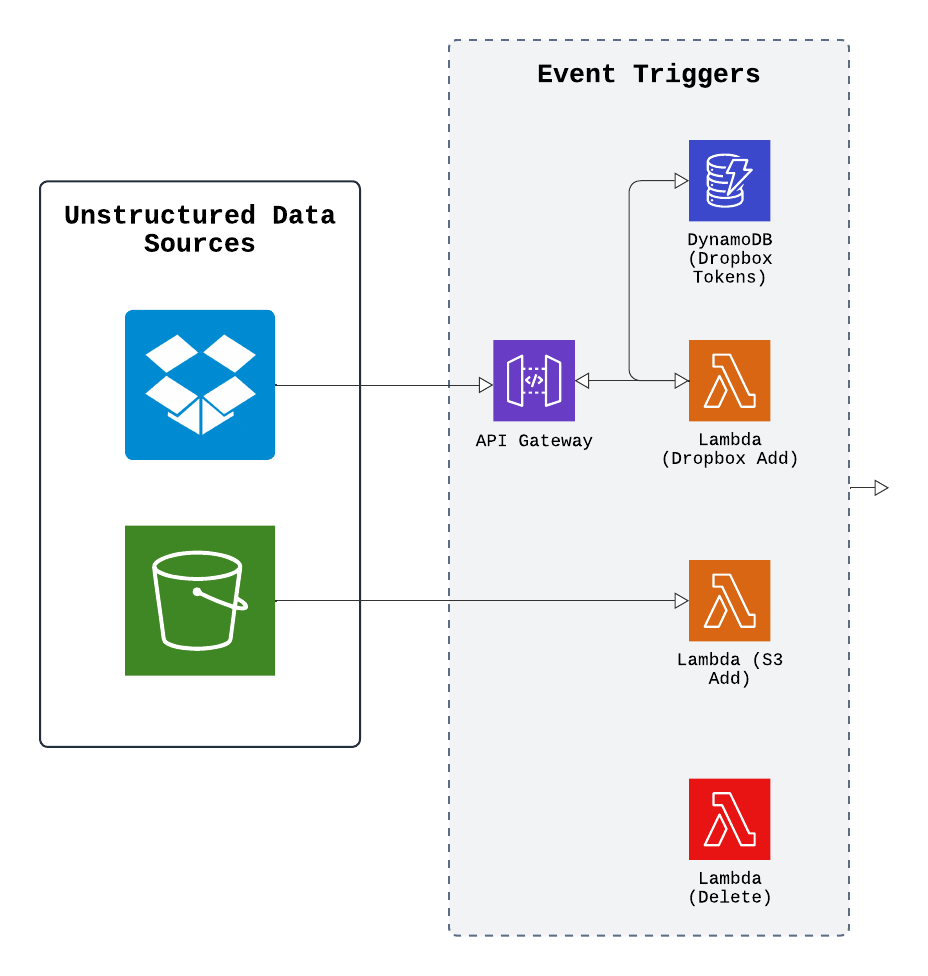

In the source subsection, our goal was to develop an architecture that would connect a user-provided source to the application infrastructure. This system would also automatically ingest documents or delete vectors based on whether a document was added, deleted, or updated in the source. The automatic detection mechanism was implemented using an event-triggered workflow based on notifications.

We initially began by exploring AWS S3 as a source option because it is a widely-used, reliable storage platform with built-in integration across other AWS services. Another key feature that stood out was its ability to generate detailed notifications whenever a document is added or deleted. This made it easier to design the application to respond to those events and trigger the appropriate workflows or actions in the system. We found a well-suited solution in AWS Lambda, a serverless compute service that runs code without the need to provision a server.

For example, when a deletion event occurs, it triggers a Lambda function that removes all vectors associated with the document, using a method tailored to the specific database provider. For new documents, a different Lambda function is triggered, which extracts the document's filename and adds a new job to the queue. Jobs are then processed by the ingestion engine. If a document is added but already exists in the source, it is treated as an update. In this case, the same Lambda function for additions is triggered, but it first deletes the old vectors before adding the new ones. This approach allows us to synchronize the documents in the source with their corresponding vectors in the destination, all through event-triggered workflows.

Other applications might use methods like continuous or periodic polling to fetch changes from the source and push new events. Polling can offer some advantages, such as providing more control over the frequency of updates and ensuring reliable processing by checking data at regular intervals. However, it requires additional services to manage the polling logic and the pushing of notifications. While AWS services like Simple Notification Service could help with this, the added complexity did not seem like a worthwhile tradeoff for our intended use case. Polling can also be less responsive than event triggers, as it depends on the frequency of checks, which can introduce delays in detecting changes. This can lead to stale data, which runs counter to our goal of timely and rapid updates.

One key advantage of using S3 buckets as a source is their native integration with other AWS Cloud services. However, we recognized that many other file storage platforms might not integrate as easily and would require additional configuration. For example, when integrating Dropbox, we encountered a major roadblock: Dropbox no longer offers permanent API keys and instead requires OAuth for authentication. While it was possible to authenticate Dropbox permissions and establish a connection to run the ingestion pipeline, the authentication would expire after a few hours. This meant the user would need to re-establish the connection, which would lead to a poor user experience.

To address this, we designed a workflow that guides users through generating a Dropbox refresh token. This token, along with the current API key, is stored in a DynamoDB database. When a user adds a file to their Dropbox folder, Dropbox sends a notification to an endpoint set up using a Webhook API Gateway, which triggers a Lambda function. This Lambda checks the API key in the database to see if it has expired. If it has, the Lambda uses the stored refresh token to automatically generate a new API key, ensuring the connection between Dropbox and the application remains intact. This approach provides a smooth, uninterrupted experience for the user.

5.2 Ingestion

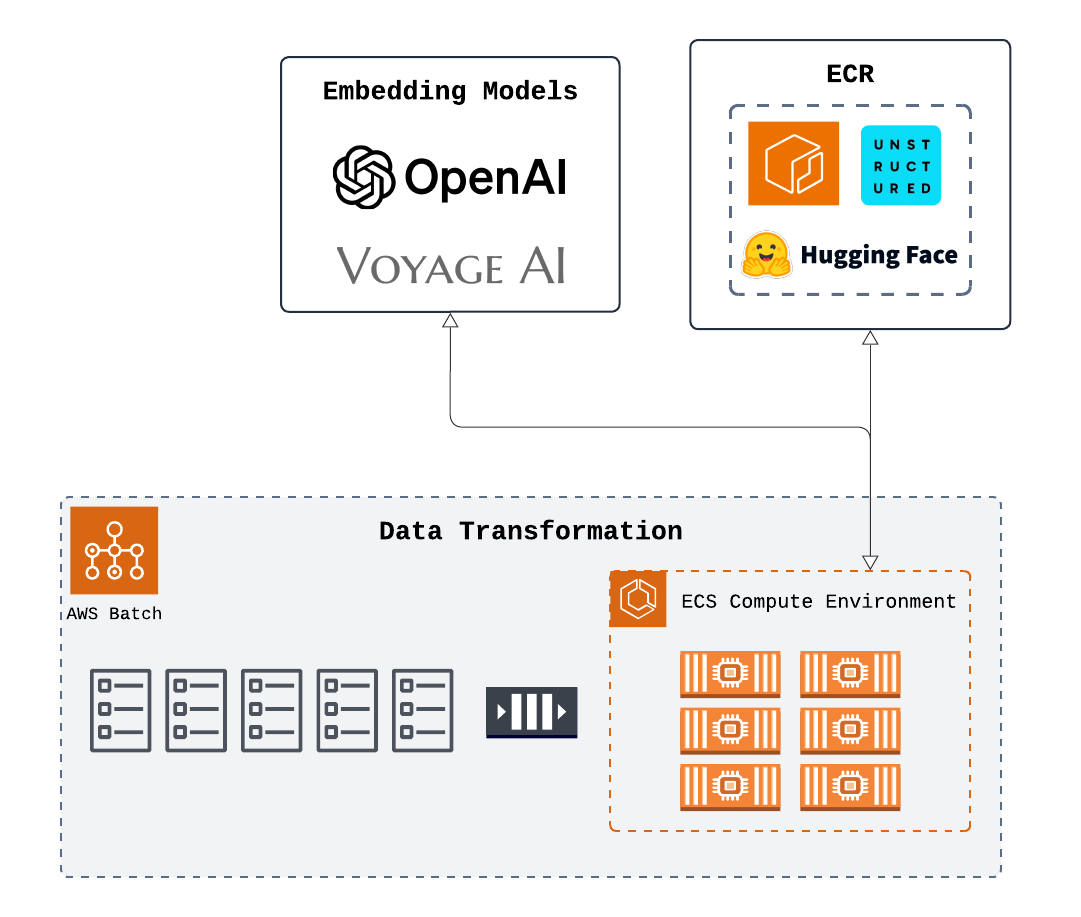

In the ingestion subsection, the document from the previous section is processed using a script based on Unstructured.io’s open-source library’s “data ingestion”. This process generates a set of vectors, which are then added to an externally managed database, which will be described in the “destination” subsection. To generate the embeddings, users have the option to either run the embedding model in the container as part of the ingestion script (such as when using a HuggingFace model) or outsource the generation of embeddings to a third-party provider (such as OpenAI).

Our original prototype used an AWS Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) instance, a scalable virtual server, to run the ingestion code. This approach allowed us to perform the ingestion without managing physical hardware. While this successfully ran the ingestion script as intended, we recognized that the ingestion itself does not produce any data that needs to be stored or retained, making the continuous availability of the EC2 instance unnecessary. We instead aimed to find a service focused solely on executing the ingestion code and would dissipate after completing the job. Thematically, containers were a good fit for our intended use case because they could be generated quickly, perform a task, and then terminate. Each new document would be processed in its own containerized environment so that multiple containers can run in parallel. This setup also ensures that an error or failure in ingesting one document would not affect the on-going processing of other documents that were currently running.

A single container could only ingest a collection of documents one at a time so we quickly realized that the lack of parallel processing would significantly bottleneck the ingestion process for a user’s typical document load. While processing speed could be improved to some extent by vertically scaling the container (increasing its compute capacity), we recognized that a horizontally scaled solution would be necessary to handle larger batches of documents. To address this issue, we planned to process each document in its own container and handle the orchestration through AWS’s Elastic Container Service (ECS) in combination with AWS Fargate to manage the compute resources. This solution was mostly effective, but when processing larger batches, the amount of containers began to become overwhelming. It was also difficult to monitor the progress of individual tasks. Additionally, processing a large number of documents simultaneously could potentially add strain to the destination database if many documents complete around the same time and attempt to push vectors to the database within a similar time frame.

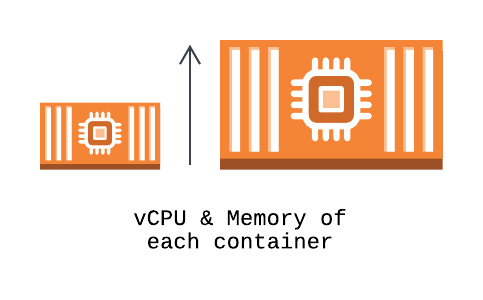

Ultimately, a balanced approach was achieved by incorporating AWS Batch. This service allowed us to define the ingestion of each document as a job, which enters a job queue. The queue manages the jobs, ensuring they only run when there is available space and resources in the compute environment. AWS Batch allowed us to add horizontal scalability by enabling multiple documents to be processed in parallel. It also gave us the flexibility to customize the memory and CPU resources for each container, making it easy for users to scale vertically if needed. Additionally, the compute environment itself can be customized, allowing more jobs to run simultaneously and further increasing horizontal scalability.

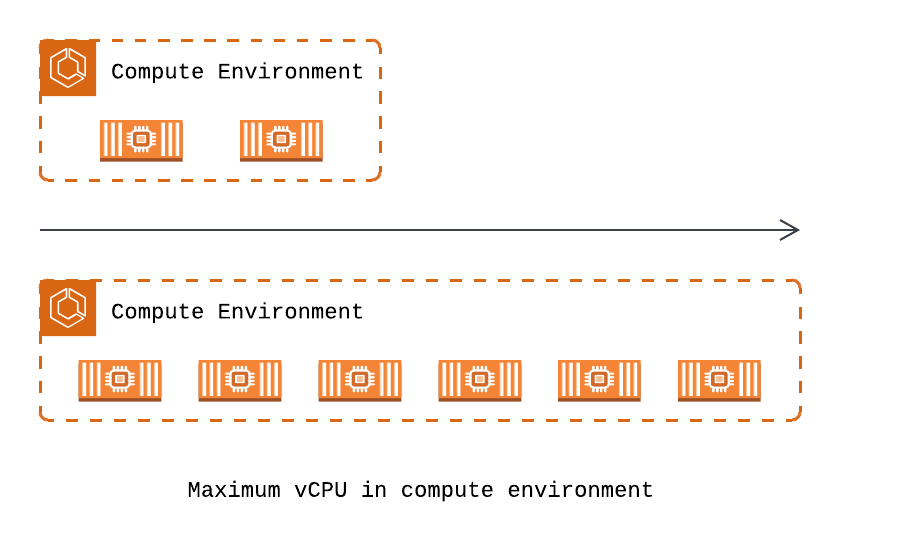

Vertical scaling of a container by increasing the vCPU and memory allocation, allowing for more processing power within a single container

Horizontal scaling of the compute environment by increasing the maximum vCPU, enabling the simultaneous execution of multiple containers to process more tasks in parallel.

During the ingestion process, we found that there were two areas that were opportunities for improved productivity. The first was from the embedding step, which typically took the longest. For users opting to perform embedding with a HuggingFace model, this step depends on the processing power of the container. To address this, we increased the memory and CPU from the AWS default (0.25 virtual CPUs and 512 MiB memory) to the application’s default (2 virtual CPUs and 4 GB memory). The second area of optimization was the container start-up time. Containers are generated from a pre-defined image that includes the necessary packages for running the ingestion code. Instead of installing the full Unstructured.io library, we selectively installed only the minimum modules for the connectors that Splinter supports. This reduced the size of the image and, in turn, decreased the start-up time. With the implementation of both changes, the ingestion time for a 2.2 MB sample document was reduced from 3.5 minutes to just 1 minute, taking less than 30% of the original duration, representing a performance improvement of over 70%. Overall, these features of containers and AWS Batch jobs addressed our desire for a scalable method for short-lived ingestion script execution.

After data is ingested and transformed into embeddings, storing these vectors in a destination optimized for vector handling is the next critical step. This ensures fast, scalable retrieval and efficient management of the data.

5.3 Destination

Another major subsection of Splinter is the destination, where vector embeddings are stored in the user-provided database. Once the data is ingested and transformed into vector embeddings, these vectors are stored as entries in the chosen vector database. Users are required to provide their own database because knowledge bases generated by the ingestion pipeline are highly customizable and have many potential downstream uses that depend on the user’s specific needs. By leveraging their own database, users have full control over data storage, security, and access.

Splinter is designed to support a variety of databases that can store and manage embeddings: a vector database (Pinecone), a NoSQL database (MongoDB), and a relational database (PostgreSQL). Users can select the database that best fits their requirements for performance, scalability, and integration with their broader system architecture. The choice of database depends on factors such as query speed, scalability for large datasets, and compatibility with the rest of the user’s tech stack.

Vector databases like Pinecone are optimized for similarity search, making them ideal for applications such as semantic search and recommendation engines. These databases enable highly efficient retrieval of similar vectors, even across large datasets, and are designed to scale as the volume of embeddings increases.

NoSQL databases like MongoDB offer flexible, schema-less data storage that can be ideal when you need to store embeddings alongside other types of unstructured or semi-structured data, such as metadata or user profiles. This flexibility makes it a good choice for applications that need to store a variety of data formats and quickly adapt to changing requirements.

Relational databases like PostgreSQL can be used when users need to store embeddings alongside traditional structured data (e.g., user profiles, transaction logs). Though not specifically designed for high-performance vector search, these databases can be a good fit when embeddings are just one part of a larger data architecture and the focus is on maintaining relationships between structured data.

5.4 Frontend Client

The client subsection establishes a locally-deployed frontend interface which connects to the destination database to allow users to interact with their ingested data and also connects to various infrastructure components to display key metrics and progress of the pipeline.

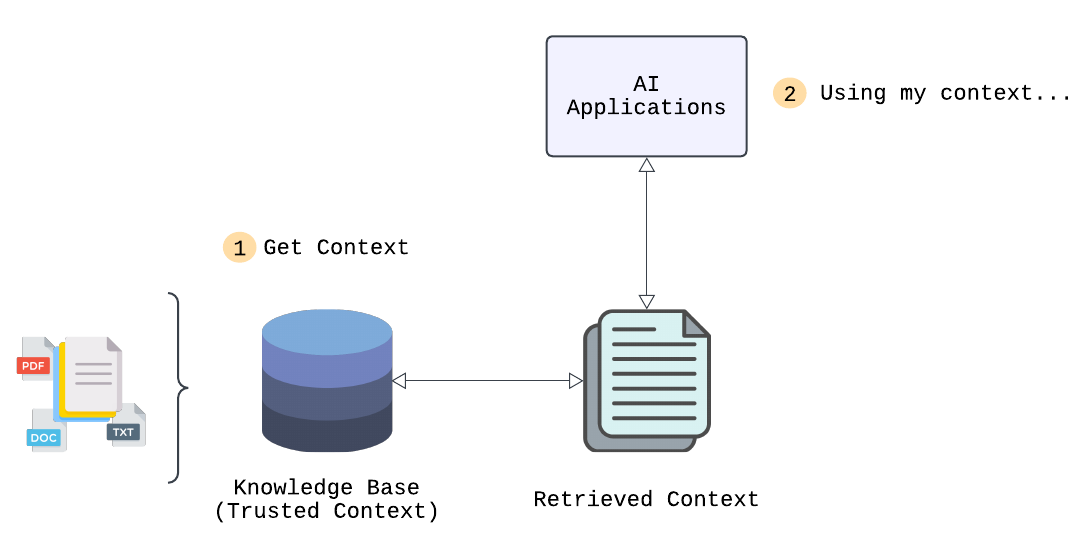

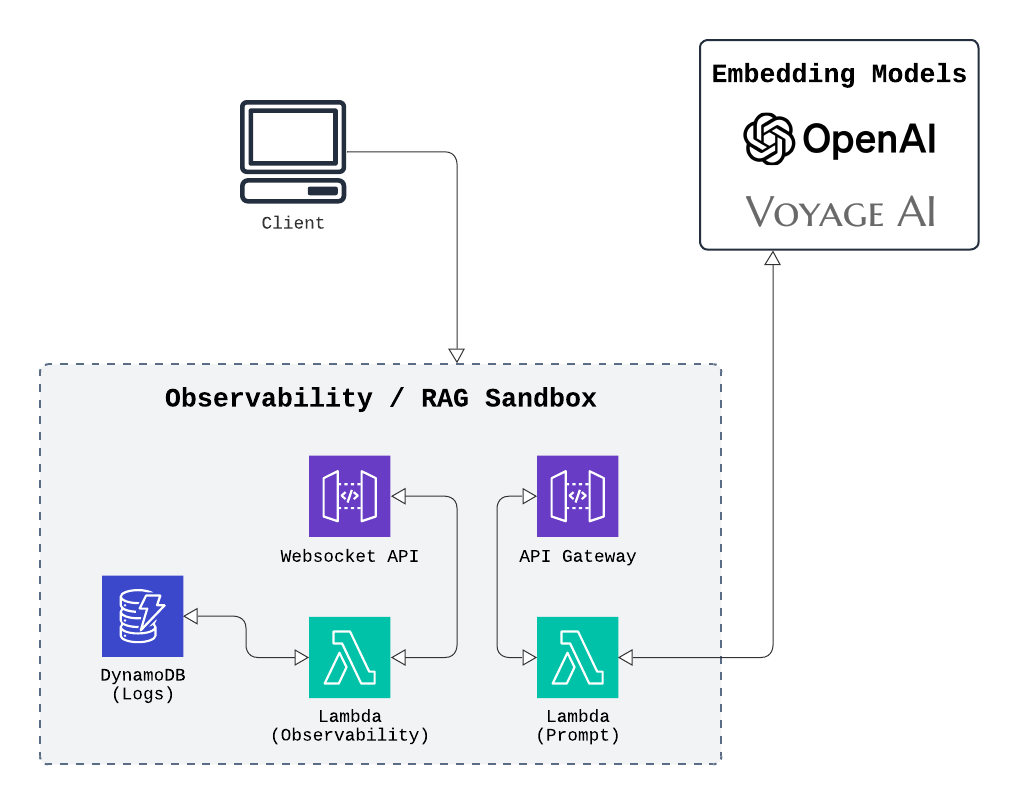

RAG Sandbox

Splinter serves as a data pipeline designed to populate knowledge bases and one common use of knowledge bases is to provide additional context for an LLM prompt through Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). In this process, relevant information is retrieved from a knowledge base and incorporated into the model’s generation process.

A critical aspect of this process is ensuring that the ingestion of documents into vectors is accurate and that the resulting knowledge base is effectively structured for downstream tasks. If the data is not properly vectorized, the information retrieved during the RAG process may be irrelevant or incomplete, leading to suboptimal model outputs. To help users ensure the quality of their data and the accuracy of their embeddings, we created the RAG Sandbox feature.

The RAG Sandbox allows users to validate the quality of their ingested knowledge base by generating a test question, which is then embedded using the same model as the ingestion process. The question is used to query the knowledge base, retrieving the top 5 most relevant data chunks. These chunks are then combined with the question to form a prompt, which is passed to the LLM. The model’s generated answer is based on the provided context, allowing users to evaluate how well the knowledge base has been built and how accurately the embeddings represent the relevant information.

This validation step is important because it allows users to detect potential issues early in the process, such as incorrect vectorization or misaligned relevance between the query and the retrieved data. For example, if the top results are irrelevant or do not reflect the expected context, it may indicate a problem with how the documents were processed or embedded.

Much like the ingestion script, the RAG Sandbox operates as a short-lived execution of code. It retrieves a question, fetches relevant chunks, prompts the LLM, and displays the response in the frontend GUI. Since no long-term data needs to be retained, we decided to implement this functionality using a Lambda, ensuring fast, cost-effective execution.

Observability Dashboard

The observability dashboard is intended to assist with monitoring the overall pipeline. The ingestion process involves multiple events, each generating useful information, but displaying every detail could overwhelm the user. To avoid this, we focused on key events that provide the most value, such as the completion of major ingestion steps (partitioning, chunking, embedding), document processing, vector uploads, and scheduled vector deletions. Additional metrics include the current count of documents and vectors in the database, as well as the number of documents and vectors processed in the current session. We also decided to track the overall job queue progress, displaying the number of jobs that are starting, running, completed, or failed, to provide better observability into the pipeline's progression. The observability dashboard was created to display these metrics in a way to allow users to have a more detailed and live update on the pipeline.

To keep the frontend up-to-date with new pipeline events, we looked for a solution which could allow constant communication between the cloud-deployed application and the local client. One option was implementing server-side events, which would propagate data from the application to frontend. However, this would require a continuously running server connection which was a thematically incongruent with our ephemeral architecture. Instead, we chose to use AWS WebSocket API Gateway, where routes activate only when new data from the application needs to be displayed in the dashboard. This allowed synchronization between the application and observability dashboard.

However, we encountered an issue where the WebSocket connection would reset if the frontend was refreshed or after prolonged periods of inactivity. This disrupted session continuity, as real-time updates to the dashboard would be lost when the connection was severed, resulting in potentially important data updates not being passed to the frontend during downtime. To address this, we implemented a database to store recent logs and metrics, ensuring that updates were persisted across frontend refreshes or disconnections.

The architecture was set up where WebSocket connect and disconnect routes are managed by Lambdas, which track client connections and handle cleanup. When key events are logged, a Lambda processes the data and updates a DynamoDB with logs and vector/document counts. Document events (e.g. addition or deletion) update DynamoDB and send real-time messages through the WebSocket API to update the dashboard. Lastly, a WebSocket route triggers a Lambda to fetch the latest data from DynamoDB, AWS Batch, and the vector database during initial load or refresh, ensuring session persistence.

5.5 Full Architecture Diagram

Having outlined the core architecture, the next step is to focus on expanding Splinter’s capabilities. Future developments will enhance the platform's versatility and scalability, enabling it to support a wider range of use cases and integrations.

6. Future Work

Splinter fully supports managing document updates and deletions with AWS S3 as a data source through built-in integrations. While we also support Dropbox as a data source, the available features are currently more limited due to constraints in the notifications provided by the Dropbox API. However, we recognize that broadening support to non-S3 sources is crucial for increasing the platform's flexibility and accommodating a wider range of user needs. Many users may prefer to integrate with storage solutions they already use, whether due to company infrastructure or personal preferences. Future updates will focus on handling additional document options for non-S3 sources.

For destination databases, Splinter offers three options: Pinecone, MongoDB, and PostgreSQL. Full ingestion functionality is offered for all of these database options. The Pinecone platform natively includes vector querying to search the database for top matches, which is necessary to drive the RAG Sandbox. However, MongoDB and PostgreSQL require third-party tools or manual indexing to accomplish vector querying. We therefore focused on Pinecone support for the RAG Sandbox in the initial launch but plan to extend functionality to other databases in future versions.

Overall, Splinter’s future enhancements will aim at broadening source and destination support.